|

| |

Home

Ondas del Lago

Ondas del Lago

Contributed Content

Contributed Content

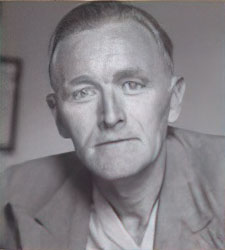

Peter

Tveskov Peter

Tveskov

|

Peter Tveskov has had a long association with Venezuela,

having spent much of his youth there after the Second World

War and returning years later to work. His “recuerdos” of

Venezuela over the years are extensive because of the many

years he lived there.

Peter's bio is as follows: Born in Denmark, Peter moved to

Venezuela at age 14 in 1948. He graduated from Yale

University 1956 with a Bachelor of Engineering degree.

After becoming a US citizen in 1960 in Del Rio, Texas, Peter

worked ten years for the Oilwell Supply Division of US

Steel Corporation in West Texas, Venezuela, Brazil and

New York City.

In 1966-1996, he was director of facilities and a management

consultant at Yale University, Wesleyan

University in Middletown, Connecticut, Brown

University, Connecticut College, Milton

Academy, Vassar College, Choate-Rosemary

Hall, Monmouth University, Bryn Mawr

College and the Ethical Culture School in New York

City.

Since his retirement, Peter has done part time construction

project management, has been a Group Leader on five Elderhostel/Scandinavian

Seminar trips to Scandinavia, and authored a book entitled “Conquered,

not defeated - Growing up in Denmark during the German

Occupation of World War II ”.

Married fifty years to Judith Santamauro, he has four grown

children scattered all over the continent, and three

granddaughters. He currently resides in the Short Beach

section of Branford, Connecticut.

We're extremely fortunate that Peter has taken the time to

write about some of his memories of Venezuela, thereby

preserving them, and that he has very generously allowed us

to share some of those memories here.

While the writing

below recounts Peter's personal experiences in Venezuela, he

has also written the intriguing story of his father's

experiences as a Danish immigrant in Venezuela during

earlier years after he was stranded there by the German

occupation of Denmark in 1940.

A European Immigrant in Venezuela1938-1975

Click to read an account of Alex Tveskov's experiences in

Venezuela

Lastly, after you've read Peter's stories on this page as

well as the compelling account of his father's experiences

in Venezuela as an immigrant, please click on the title

below to read Peter's reflections about his last visit to

Venezuela in 1964 as well as his feelings about the current

unfortunate state of affairs that exists in Venezuela today.

Click to read

Venezuela since the 1960's

|

|

My

relationship with Venezuela has three phases: My teenage

years in the country, my professional years there and

the present.

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Venezuela in

the 40s and 50s

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Three

days after my fourteenth birthday I arrived in Maiquetia

from Curaçao after a three day trip via KLM from

Copenhagen, Denmark. We had flown from Copenhagen to

Amsterdam in a DC-4, from Amsterdam via Glasgow, Gander

and New York to Curaçao in a Lockheed Constellation, the

“Eindhoven”, to Curaçao and the last leg, after a night

in a very hot KLM hostelry – a

former US Army barracks - in another DC-4, set up for

half cargo and half passengers. The passenger half was

lined in black material of some sort and it was really

hot.

I arrived in

Maiquetia, was received by a friend of my new stepfather and

after a night at the hotel El Conde, owned by PanAm,

my papers were arranged with the authorities and I was put

on an Avensa DC-3 and proceded to

San Antonio del Táchira via Barquisimeto, Valera and Mérida.

I did not know when I was to get off the plane and nobody on

the plane spoke English, let alone Danish, but I do remember

being offered my very first Coca Cola on that flight.

For the record, it was probably Joseph Stalin’s fault that I

even went to Venezuela in the first place. My mother had

recently married Axel Tveskov, a Dane who had gone to

Venezuela before the war and had become marooned there by

the German invasion of Denmark April 9, 1940. The original

plan was that I was to finish my schooling in Denmark, but

with the advent of the blockade of Berlin by the Soviets and

the very real possibility of World War III breaking out, it

was decided that I was to leave the rationed gloom and

darkness of post war Denmark and head for Venezuela.

So off I went and settled in Palmira in the state of

Táchira, where my stepfather had built a cement plant for

the Delfino family and been asked to manage it.

We lived in a beautiful quinta in Palmira with a

fantastic southern view over the valley of the

Torbes River.

There is a mountain on the far horizon and to this

date I wonder what is its name and where is it

located? In Venezuela? In Colombia?

Because of his position as director of a major local

enterprise, my stepfather was a member of the local

society. He belonged to the local clubs where we

socialized with the governor of the state, Señor

Romero Espejo – later murdered under the Pérez

Jimenez dictatorship and the military commandant of

Táchira, major – Comandante – Mario Vargas, who also

eventually ran afoul of PJ, but survived. Even PJ

himself visited our home. I remember him as a short,

pudgy and quiet colonel sitting by himself nursing a

drink!

I suppose it was a pretty decadent lifestyle, and

certainly different from Denmark!

We made frequent trip across the border to Cúcuta to

go shopping. The Venezuelan money was worth more

than the Colombian peso and it was possible to buy

imported goods, as well as liquor, in Cúcuta due to

the high tariffs imposed on imports in Venezuela.

There were also good restaurants and the Colombians,

albeit in many ways like the Venezuelan Andinos,

seemed more cultured. As an example, there were

several Colombians employed at my stepfather’s

factory and they always referred to my mother as “su

señora Madre”. The Spanish spoken on the other side

of the border was also closer to Castilian Spanish

than the language spoken in Venezuela; in fact I am

told that most Castilian Spanish spoken in Latin

America is spoken in Medellín, Colombia.

As in most countries there were distinct regional

differences between various areas. The Andinos – or

gochos as they were known by other Venezuelans –

tended to be quiet and dignified, usually white with

a touch of Indian, especially in the mountain

villages. There used to be a saying that “se

usan Ustéd hasta a los gatos” in the Andes, as

the second person “tú” was rarely used except

between parents and their children. The children

would address their parents as “Ustéd”.

The “Maracuchos” from Maracaibo spoke a more

sing-song Spanish characterized by using the second

person plural – vós and Vosotros – among each other.

Supposedly this accent comes from Southern Spain.

In Caracas the Spanish was much less formal and in

many ways similar to Puerto Rican Spanish – or even

today’s Spanglish. For instance, the “r” in

the middle of a word is often pronounced closer to

an “l”. In the East and on the Llanos the language

was less differentiated from “official” Spanish,

which incidentally in those days was always referred

to as “Castellano”, never “Español”!

Ethnically there seemed to be a greater division

between white Criollos and blacks and mulattos in

the Coastal regions and Caracas, while the Llaneros

generally appeared to be more mestizos.

There was a tremendous influx of European immigrants

right after World War II, especially from Italy,

Spain and Portugal and it seemed that most small

businesses, bus lines and stores in Caracas belonged

to recently arrived Southern Europeans.

Caracas had begun its explosive expansion. On that

my first visit I remember seeing the big hole in the

ground from where the Centro Bolivar’s two

skyscrapers were to emerge! Otherwise, the city was

still basically its old Colonial self.

Venezuela was just then emerging from the hangover

of the thirty-five year Juan Vicente Gomez

dictatorship. It had been followed by the

presidencies of two other generals from Táchira:

López Contreras and Medina Angarita and with their

leadership had evolved into the first true

democratic experiment, the novelist Rómulo Gallegos

having been elected president in 1947.

Three major political parties were active: Acción

Democrática (AD) led by Romulo

Betancourt, COPEI (The Christian Democrats)

led by Rafael Caldera and URD whose leader

was Jóvito Villalba.

Both Betancourt and Caldera eventually were elected

president after the fall of General Pérez Jimenez,

while URD’s claim to fame was that they

actually beat Pérez Jimenez’ “official” party in the

fixed elections in 1951! Did not do them any good as

Pérez Jimenez then cancelled the election results

and declared himself the winner.

However, Rómulo Gallegos was ousted by a military

coup in 1948 and succeeded by a Junta Militar de

Gobierno composed of three colonels: Delgado

Chalbaud, Pérez Jimenez and Llovera Paez. Delgado

Chalbaud was kidnapped and brutally assassinated in

1949. While the actual murder was carried out by a

political adventurer, “General” Urbina, who was shot

“trying to escape” afterwards, fingers were and are

pointed at Pérez Jimenez, who ended up running the

country as dictator till 1958.

It is historically significant that the three

colonels were products of Gomez’ new national

Military Academy in Caracas, established in his

successful attempt to do away with the individual

federal states’ militias and thus preventing local

war lords, usually from Táchira, as was Gomez, from

marching on Caracas and starting another civil war,

of which there were many!

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Venezuelan

Currency

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

The

Venezuelan currency had been revised introducing the

Bolivar as the basic unit. However, the old

nomenclature was still commonly used, a nomenclature

based on the Venezuelan Peso and Real. The coins,

except for the two smallest denominations, were all

silver, the largest coin being identical in size and

silver content to the European “Crowns” and the US

silver dollar. However, while this coin was worth

Bs. 5, the US Dollar could be bought for Bs. 3.35 in

the forties, as the Bolivar had appreciated. Some

gold coins were still in circulation, most commonly

the Bs. 20 coin which was identical in size to the

Bs. 1 coin, except that Bolivar’s face pointed in

the opposite direction, this to discourage people

from gilding the silver coins and passing them as

gold.

As the silver coins were identical in design, albeit

not in size, and for some reason did not show any

numerical values, one had to be familiar with their

names and monetary values, sometimes that could be

difficult.

|

• Bs 5:

Similar in size to the US silver dollar,

called the “Fuerte” or “Cachete”:

“Cheek”, as it showed Bolivar’s face in

profile.

|

|

|

| |

|

• Bs.2:

Smaller than a US 50 cent coin. Called the “Peso”.

|

|

|

| |

|

• Bs.1: About

the size of the US 25 cent coin. The base

unit of the new currency system.

|

|

|

| |

|

• 50 centimos:

The “Real” from an older system, a

name still widely in common use in the 40s

and 50s.

|

|

|

| |

|

• 25 centimos:

Known as the “Medio” as it was half

of a “Real”. This could be very

complicated when one went shopping. For

instance, a pack of cigarettes cost 75

centimos, but was quoted as “Real y

Medio”!

|

|

|

| |

|

• 12.5 centimos:

A nickel copper coin known as the “Locha”

as it was Un Octavo of a Real! Did I lose

you yet?

|

|

|

| |

|

• 5 centimos:

Another small nickel copper coin still in

use in the 40s and 50s. Sometimes known as a

“pulga”: Flea.

|

|

|

In the 1960s the denomination of the coins were

finally printed on the coins and eventually the

silver coins disappeared altogether, to be replaced

by coins made of semi-precious metals, following the

lead of the US and our coins.

By today, inflation of course has made coins

completely irrelevant. By the time I returned to

Venezuela to work in the sixties, the Bolivar had

stabilized at Bs 4.45/$, but today it is around Bs

2,400/$, creating price tags that are hard to

interpret by us old-timers!

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

My

Venezuelan Education

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

When leaving Denmark I was

in the eight grade, which corresponded

academically to the US third year of High

School. Besides foreign languages – English and

German – (After all, nobody speaks Danish! Even

in that small country a city boy from Copenhagen

was hard pressed to understand the Jutland

dialect, only a hundred miles or so away) we had

begun algebra, trigonometry, physics and

chemistry. I was fluent in English and German,

but of course had no Spanish at all.

So I went to the US right after New Years in

1949 and attended New

York Military Academy in

Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY. I was placed in the

eight grade which academically was way behind

where I had been in Denmark. I did learn how to

make a hospital corner on a bed, do close order

drill and how to field strip a Springfield 30-06

army rifle, as well as American History, which

was a totally new subject for me. One thing that

I will never forget is that while our history

book was quite detailed about World War II,

there was no mention at all about the Holocaust,

and this four years after the end of the war.

So it was decided that I was to attend a

Venezuelan boarding school the next term. The

school chosen was the Colégio de San José de

Mérida, a two hundred year old Jesuit

school attended by the children of the

Venezuelan aristocracy from Caracas, Maracaibo,

San Cristobal and other major cities.

I was placed in the Third Year of Bachillerato,

roughly equivalent to where I had been in

Denmark. In order to remain in that class I

needed to take an equivalency exam in ninety

days, covering two years of Spanish language and

literature. I was drilled in those subjects

every afternoon by one of the Jesuit priests and

passed the exam, which took place in the public

high school, the Liceo and was given by the

teachers of that institution. Speak of total

immersion!

So Spanish in effect became my first language

until I came to the US in 1952 and had to make

yet another change.

I spent two years at the Colégio de San José and

I can only say that they were great years. First

of all, Mérida is an absolutely beautiful place

and with its snow capped mountains quite a

change from the Danish lowlands. By the way, do

not picture Denmark as flat; anyone who has

ridden a bicycle there can attest that it

definitely is not!

The boys that I lived and studied with became

good friends and as the future leaders of

Venezuela, I managed to keep in touch with some.

By now these friends have passed on. The best

known was probably Jorge Olavarria who became

Venezuela’s ambassador to Great Britain,

historian, senator and presidential candidate,

who ended up as a thorn in the side of Hugo

Chavez as a columnist for El Nacional until he

died a couple of years ago.

Among the priests, several stood out. The rector

Fr.Jose Maria Velaz, a Chilean, who eventually

started the educational organization for grown

children of peasants and workers called Fe

y Alegría, very similar to the Danish

Folk High School idea. Fr.Carlos Reyna SJ, an

engineer and the only Venezuelan priest in the

school eventually became the first rector of the

Catholic university in Caracas: Universidad

Católica Andrés Bello. Most of the

priests were Basques from Spain and very much

against Francisco Franco, the Caudillo of Spain.

It was enlightening to me to find out that not

all Franco’s opposition were Communists! These

men certainly were anything but. So another

culture was opened up to me: The Basque.

In December 1950 a DC-3 of AVENSA left

Mérida due for Maiquetía with 27 students of all

ages from the school aboard. It got lost in fog

and crashed into a mountain near Valera, killing

all aboard. A month or so after the crash a

group of volunteer students, including me, went

to the crash site to recover our friends’

belongings. We also brought the plane’s props

back down and they were incorporated into a

memorial monument at the spiritual retreat San

Javiér de Valle Grande, built by the

Jesuits outside of Mérida. They are still there,

perpetually bathed in a small waterfall

symbolizing the eternal tears of the survivors.

A beautiful spot, well worth a visit.

In

March 1951, a group of

seniors went to the

acccident site from where we

brought back the plane's

propellers, which were

installed in the retreat

house which the Jesuit

fathers built at San Javier

del Valle, near Mérida, in

memory of the boys. We

brought a large cross to the

site, which was installed

there.

|

|

|

A

temporary

interruption

near Chachopo en

route to the

accident site -

a very common

event on the

Carretera

Transandina.

|

Carlos Rivas

Cols, a

classmate and

friend, in the

typical type of

bus used in the

Andes in those

days that took

us from Mérida

to Esquque, from

where we made

the rest of the

trip on foot.

Carlos Rivas

became the first

Venezuelan PhD

in Biology, his

area of research

being

bioluminescence.

He is now

emeritus.

|

|

|

In 1951 my folks moved to Caracas where I

entered the Liceo Andrés Bello for my

5th year of High School or Pre-Universitario,

from where I graduated in 1952. That year was

quite chaotic due to the political situation

precipitated by Pérez Jimenez’ brutal

dictatorship. The students at Liceo Andrés

Bello were middle class Venezuelans and the

children of recent immigrants, a different group

than my friends from Mérida. There were several

strikes which we foreigners – “musiús” as they

called us – could not in any way be identified

with unless we wanted immediate expulsion from

the country.

One day returning from lunch I met a large group

of students being chased down the street from

the school by a machete swinging policeman. I

kept on walking through the crowd; the cop gave

me a curious look and continued his chase.

So I graduated and became a Bachillér de Físicas

y Matemáticas, and as Pérez Jimenez had closed

the universities, I came to the US to study

engineering, but that – as they say – is another

story!

One comment on the difference between the

Venezuelan, Danish and US educational

philosophies – at least back then: The

Venezuelan & Danish systems were very much based

on absolutes and root learning. It was quite an

enlightenment for me to come to the university

in the US and be expected to disagree with the

professor, as long as one’s reasoning and

research were sound.

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Teenage

social life in Caracas

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Dating as we know it was

unknown, at least with Venezuelan girls. Young

people who knew each other well, would often get

together at someone’s house to dance to records and

if the group was larger and not so well acquainted,

the room would be well chaperoned with mothers and

aunts sitting along the walls keeping an eye on

things. On occasion one might double date with two

sisters, who could then keep an eye on each other.

So one made do.

I played soccer with a pick-up Danish team against

similar Italian and Spanish teams – on a very rocky

field I might add. I still have a scar on my knee to

prove that.

I was also involved with a Danish folk-dancing

group, but believe me; Danish folk dancing is not

intended for even temperate albeit un-air

conditioned Caracas.

Once while on vacation from college a Panamanian

friend of mine, his sister and his girlfriend and I

went to the Hotel Tamanaco’s night club.

They had advertised in “El Universal” that

the Mexican singer Pedro Vargas would perform and

there would be no cover or minimum charges. So we

enjoyed a lovely evening listening to Pedro Vargas

singing “La qué se fué” and other

favorites, dancing and each consuming a coke. Well,

the bill arrived and it included both a cover and

minimum charge! Fortunately we found a copy of “El

Universal” and proved to the head waiter that

we had been misled, so we avoided washing dishes or

whatever the local penalty would have been for not

paying a night club bill!

Through a young lady from Spain, with whom I worked

during the Christmas vacation of my last year in

high school, I was also invited to the Galician

social club, the “Lar Gallego” where I

learned to dance to the Galician bagpipe music!

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

The next

phase

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

After receiving my engineering

degree in 1956 I went to work for the Oilwell

Supply Division of U.S.

Steel Corporation (now National

Oilwell Varco), as well as got

married and had two little Texans born in Odessa.

After four years working mainly in Odessa, Texas, I

was sent to Venezuela as District Engineer for Oilwell –

known as USSI Ltd. in

Venezuela - based in Anaco.

The company had built a very nice little camp with a

warehouse and office, and three lovely quintas,

appropriately named Ruth, Carole and Nancy after

the wives of three big shots from Dallas. Fair

enough, I suppose.

For awhile Oilwell also

had an office and warehouse in Maracaibo where I did

vacation relief a couple of times, thus getting

familiar with the Maracaibo end of the Venezuelan

oil fields.

One thing that stands out was that when a vendor

called on the Shell headquarters,

one was expected to wear a coat and a tie! In

Maracaibo yet. At least the building was

air-conditioned.

The bridge had yet to be built and it was always a

welcome relief to be able to get on the ferry at the

end of the day and sip a cold “Polar” on

the way back to Maracaibo from the east side of the

lake!

A friend took me to the local TB sanitarium where I

purchased some very nice red placemats and napkins

embroidered by the patients, which we still have and

use.

In Anaco our biggest client was Mobil and

their Campo Norte was pretty much the center of

everyone’s social activities. There were a lot of

nice people in Anaco, clients and competitors both –

our camp was right next door to National

Supply on the Carretera Negra leading

to Puerto LaCruz.

Amazing to think that those two major competitors

eventually merged into National-Oilwell,

sort of like Ford and General

Motors merging!

I was mainly involved with the development,

installation and operation of Oilwell’s

hydraulic subsurface pumps with Mobil.

It was a way to get the very heavy oil out of the

ground, not always successful. I had a can of that

crude sitting on my desk upside down. It never did

flow out!

We were of course also involved in the sales and

service of all of Oilwell’s

other products from sucker rods through secondary

recovery pumps to entire drilling rigs.

On one occasion one of the local drilling

contractor’s rigs burned to the ground. They ordered

a new rig from us – lock, stock and barrel. My boss

took the next Avensa Convair

to Caracas to call Dallas to place the order as

telephone service was pretty much non-existent in

Anaco. The order was placed and the rig eventually

delivered, but my boss was put on the carpet for

having spent the money to fly to Caracas!

Without getting into ragging on one’s former

employer, they did have a certain provincial point

of view. For one, they had given us VWs as company

cars. The reason was that VW in Germany was a big

customer for US Steel steel

sheets. Try to take a toolpusher from West Texas out

to lunch in your Beetle while trying to convince him

that US products are better than the European

product just entering the markets back then! Not an

easy sell.

Once a group of big shots from Pittsburgh and Dallas

flew into Anaco in the company Vickers Viscount – a

British turboprop plane!

We also had a 1958 Chevy two door station wagon with

standard shift and no radio or air conditioning.

Enough said. After my wrecking the last Beetle, the

big boss in Dallas found a second hand 1958 Pontiac

V8 with all the bells and whistles which he sent us.

Just try to get spare parts for a Pontiac V8 in

Eastern Venezuela in 1961. Not easy.

By the way, we were not the only ones experimenting

with unusual cars. Mobil bought a bunch of English

Fords. Nice looking cars, but not really meant for

caliche roads!

Speaking of provincial, they sent an engineer down

from the Oilwell factory

in Pennsylvania to work on a problem with the

hydraulic subsurface pumps. He was a rather frugal

Pennsylvania Dutchman and found it outrageous that

we ate lunch in the Texaco dining

hall in Mata or wherever it was and had to pay Bs.5

for the meal. The next day he demonstratively packed

a ham sandwich and brought it with him and suggested

that I do the same. I answered, that in a place

where a dead body had to be buried within 24 hours,

I wasn’t about to eat a ham sandwich that had sat in

my un-air conditioned car for any length of time.

The next day he joined us in the Texaco dining

hall.

On the positive side, he borrowed my car one weekend

to go to the beach at Puerto LaCruz. When he

returned he told me that he had filled up the tank

using the Mobil credit

card in the glove compartment. As there were no

credit cards in Venezuela then, I expressed some

surprise. He showed me the card. It was a gate-pass

to Mobil’s Campo Norte in

Anaco.

So we got into the rhythm of living in Eastern

Venezuela. Shopping was no great problem as

Rockefeller’s CADA supermarket

was in the local shopping center. Our little kids

started nursery school and kindergarten in the Escuela

Anaco in the Mobil camp.

We learned how to play decent bridge and got

involved with the little theatre, also in the Mobil club.

That was fun, except when rain hit the sheet metal

roof during a performance and the audience had to

crowd up around the stage to be able to hear

anything.

Due to the coincidence of Venezuela’s and the US

independence days being back to back, there always

were big back to back parties July 4-5.

After one of these parties another young couple and

we decided to go for a swim in the pool – fully

dressed. (Don’t ask). I did carefully fold up my

brand new dinner jacket on the side of the pool only

to have the ladies stand on it to drain when the

swim was over. When we got home, our maid Adelaide

very helpfully put the dinner jacket in the washing

machine.

So who was around Anaco in those days? Mobil of

course, as well as Gulf around

San Tomé. Santa Fe Drilling and H&P were

there, as well as a multitude of service and supply

companies. Texaco had

fields east of El Tigre as well at Roblecito near

Las Mercedes west of Valle de la Pascua, only

accessible by a long, dusty ride on a dirt road. We

installed a couple of large compressors there.

The airport was served daily from Caracas by Avensa Convairs

and Fokker F-27s, with a DC-3 that continued on to

Canaima with tourists on the week-end.

The daily trip to meet the Convair was a necessary

tradition, as we also picked up our aero-paquete

with the mail forwarded from Caracas.

On occasion we would visit the new Sears in

Puerto LaCruz and have lunch there and a great

advantage for us was that my parents lived first in

Ciudad Piár by the Orinoco Mining

Company iron mines and later in Ciudád

Bolivar. They thus got to know their first two grand

children for the first time.

To reach C.B. one drove about 200 km, first to El

Tigre and then 120 km on an absolutely straight road

with only one slight dog leg in the middle to

Soledad where one crossed the Orinoco on a barge

pushed by a tugboat. That involved a maneuver where

the barge had to be turned around in mid stream in a

strong current. It is no accident that Ciudád

Bolivar’s original name was Angostura: The narrows!

Business however, was slowing down as

nationalization was on the horizon. The oil

companies were not importing any more new equipment

than what was absolutely necessary, as they expected

to lose it in the near future.

That of course meant that we did sell a lot of spare

parts, even big stuff. Emergency deliveries were

made by RANSA C-46s

directly into Anaco. Once I had to deliver a bull

gear for a mud pump in our VW pick-up truck to a rig

somewhere. The front wheels of the VW were barely on

the ground with that load in the back. The

speedometer only went to 100 kmh and the needle was

on the peg. One couldn’t keep a drilling rig

waiting.

We all went home for a month in the summer and the

tradition of course was to stock up on new clothes.

Everyone had the same Samsonite suitcases.

Once my boss and his family came back from vacation,

opened the suitcase only to find someone else’s

dirty laundry! Fortunately the switchees were honest

people, found some Oilwell catalogues

in the suitcase with all the new clothes, called Oilwell in

Dallas and the exchange was made.

On the minus side, hepatitis was endemic. My wife

went home a week or so early on vacation only to

send me a telegram that she was in the hospital with

hepatitis! We had had a despedida for her, so I had

to advise all the guests and round up all the gamma

globulin shots in Eastern Venezuela for them.

Awkward, to say the least and not very hospitable.

The tragic part about the hepatitis was that many of

the men got it, would treat it as a bad flu only to

have it come back and sometimes kill them.

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Bureaucracy

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

At

age sixteen I had been issued a cédula de Identidad,

in those days a mini passport with a convict-style

picture with a number hung around your neck, finger

print etc.

When I eventually was going back to Venezuela to

work I was told by the consulate in New York to

forget about that cédula, so when we arrived in

Venezuela my wife and I were issued new cédulas.

Shortly after that I was arrested, as I “already had

a cédula”. So I went to Caracas to try to straighten

up this mess, not easy, as I had changed my

citizenship, my name - when being naturalized – my

profession and last but not least: My “estado civil”

– being married and all! I could handle all but the

last issue, so I returned to Anaco with my new

cédula – with the old number – and the shocking

surprise to my wife that I was now “soltero”-

single! She of course had had no trouble getting

declared “casada” on her cédula. The local

authorities in Anaco helpfully suggested that the

easiest way for us to proceed would be to get

married locally. We started down that road only to

find out that my wife would be committing bigamy by

marrying me, as she obviously already was “casada”.

So we did it the long way, getting our Texas

marriage license translated and certified all the

way from Graham through Austin and Washington to

Caracas. By the time we received the final

documents, there were so many stamps on it that it

was hardly legible, but at least my wife was now an

honest woman and our kids legitimate – again.

An acquaintance of mine in Anaco, when applying for

his cédula, indicated that his mother was deceased.

So his full name in the cédula appeared as “John

Smith Deceased” as by Spanish custom your mother’s

last name would always be placed after your

father’s.

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Traffic

Law Enforcement

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

This was an issue that most of

us got entangled with one way or the other. For me

it was a bit easier as I was fluent in Spanish, but

not all that easy.

I had a head on collision at 4 am with a truck on

the dirt road between Aragua de Barcelona and Valle

de la Pascua. My poor VW Beetle company car ended up

pitifully in the opposite ditch, all wadded up, but

with one headlight still shining straight up in the

air. The truck driver took me home and then beat it.

So there I stood at sunrise by my front door,

suitcase in hand with blood pouring down my face.

The Beetle was not a US export model and did not

have safety glass in the windshield! My wife took me

to the Mobil hospital

where they patched me up only for me to be arrested

for leaving the scene of an accident! Luckily for

me, the truck driver had really left the scene so

the charges were dropped.

There was an infamous local cop at Cantaura between

Anaco and El Tigre who used to stop speeders –

probably with good justification. When my turn came

I told him to give me the ticket and let me be on my

way. He argued that it would be very complicated if

I got the ticket etc etc and we could settle it on

the spot, but I wouldn’t budge. He finally gave up

and said that at least I could buy him a beer! So I

handed him 2 Bs! He got furious, threw the coin at

me and got out of my car and went away. He later got

fired and set up business for himself on the road to

Maturín where on a deserted stretch in his old

uniform sans badges, etc. where he specialized in

stopping American women and holding them up for

money.

During some minor political upheaval when F-86s

of the Venezuelan Air Force buzzed Anaco, I was

crossing the Orinoco on the barge when a man in bits

and pieces of uniform stuck a carbine in my face and

demanded “mís papeles”. I had had it and demanded

his. A dumb thing to do with a carbine pointed at

you, I must admit. However, he handed me an ID from

the Ministry of Agriculture which I looked at and

then handed him my cédula and Título de Chofer, and

we parted friends.

The national highway patrol had installed radar sets

on the rear fenders of their new 1960 Chevrolets.

Rumor had it that the radar would sterilize them –

as it turned out, not that far from the truth, so

they deactivated most of them. One of them did catch

me at Barcelona and again it was suggested that we

settle the problem right there. I had little cash

with me, so I gave him a check (!) which I then

stopped payment on – again not the wisest move, as

the cop came looking for me in Anaco afterwards,

fortunately he looked in the “National

Supply” camp where my competitors

nobly covered up for me!

These stories could go on, I suppose.

One thing that was very clear was that if one was in

real trouble, the Guardia Nacional, in my

experience, always was on the up and up and could be

depended on to assist you.

The Guardia Nacional, officially known as the

Fuerzas Armadas de Cooperación, is a branch of the

Venezuelan Armed Forces instituted by Gomez, a

national uniformed police force patterned on the

Spanish Guardia Civíl and the Italian Carabinieri.

In “my day” they wore Italian-style green uniforms

with soft caps that had a visor and ear flaps for

use in the colder climes of the country.

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Transportation

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Venezuela by Rail. Now

don’t laugh! President Gomez had built quite an

extensive narrow gage railroad system. One could

take the train in LaGuaira and go to Caracas where

the station was near El Silencio. Then from the same

station through Maracay – Gomez’ favorite city where

he, according to tradition, built the hotel El

Jardín to house his 200 mistresses – to

Valencia and then to Puerto Cabello.

Another railroad was built from Santa Barbara del

Zulia at the south western end of Lake Maracaibo to

Estación Táchira by San Juan de Colón north of San

Cristobal. This railroad actually had a branch that

crossed the border into Colombia. The Caracas-LaGuaira

railroad was destroyed in the yearly floods of 1948

and the railroad between Zulia and Táchira was

abandoned some time in the forties. However, as late

as 1954 I took the train from Valencia to Caracas

and back several times, a really nice and

picturesque trip.

Pérez Jimenez built a standard gage railroad from

Puerto Cabello to Barquisimeto, carrying both

freight and passengers. I do not know if that

railroad is still in operation.

Venezuela by Road. When I arrived in

Venezuela as a teenager, most of the highways were

still dirt roads, except around Caracas and

Maracaibo. During the reign of Pérez Jimenez, the

Autopista Caracas-LaGuaira was built, cutting the

trip from 4-5 hours by switchback road to less than

2 hours. I understand that a viaduct on that road

recently was fund unsafe, rerouting traffic back to

the old road.

The new Panamerican Highway north of the Cordillera

Andina was also built at that time, making it

unnecessary to use Gomez’ old Carretera Trasandina

from San Cristobal via Mérida to Valera, a dirt road

that crossed at least three páramos – high mountain

passes – at El Zumbador, La Negra and Mucuchíes

(Pico Áquila). The road followed Simón Bolívar’s

route when he marched on Caracas during the War of

Independence and was built by convict labor,

including political prisoners. Tradition has it that

it cost one human life per kilometer.

Transportation over the roads was provided either by

private cars, camionetas such as the early Chevrolet

Suburbans that carried about 8-9 passengers, and Por

Puestos that were regular automobiles carrying five

unrelated passengers or buses.

The latter in those days were built of wood on truck

chassis and painted in bright colors. They did not

have glazed windows, but canvas curtains to roll

down in case of rain. I remember that the Línea

Primavera carried passengers from San Cristobal to

Caracas. As none of these conveyances had

air-conditioning – or heaters for that matter – and

the windows were usually open, the rides tended to

be long, tiring and very dusty.

One unavoidable feature of traveling by road were

the Alcabalas. They were permanent road

blocks manned by the Nacional, presumably to control

who and why people were traveling. They would have a

chain or wire rope across the dirt road, which they

would lower after giving you the beady eye and allow

you to proceed.

As I drove without a driver’s license for the first

four years of my stay in Venezuela, there was always

a certain tension passing through one of the alcabalas in

Táchira and Mérida, but I was never challenged.

One had to be either 18 or 21 to get a driver’s

license – I forget which - even with hanky-panky

with the “Authorities”; I did not manage to get a

driver’s license.

I did, however, learn to drive during the summer of

1949 when my stepfather was renovating a small

hydroelectric plant in San Juán de Colón and I

worked on that project. We drove back and forth in a

1947 Jeep CJ. The early CJs actually had a column

shift. It was discontinued shortly afterwards, but

until the Jeep body style was changed in the 60s,

there still was an unexplained notch in the

dashboard over the steering column to accommodate

the defunct column shift!

You can win bets with that piece of knowledge at the

next auto show!

While in high school I also drove the jeep belonging

to the Colegio de San José, as well as

their Ford panel truck and a surplus WW II Canadian

Dodge olive drab dump truck that had a canvas

covered escape hatch in the roof on the passenger

side of the cab. That particular vehicle, last I saw

it in 1960, was sleeping in the monte at the San

Javier del Valle spiritual retreat, and

probably by now has been completely overgrown and

quietly absorbed by nature.

The first “real car” that I drove – still without a

license – was my stepfather’s 1950 Nash Ambassador,

the famous bathtub model. Really a very great car.

Trivia: He also had had a 1949 Nash 600 –

woefully underpowered – and both had real leather

interiors – albeit no “Weather

Eye” heaters. So there, aren’t you glad you

asked?

Personally I had the opportunity to use all these

means of transportation over the years.

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Vignettes

of traveling by car in Venezuela

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

In 1960 my wife and I drove

from Maracaibo to Mérida, Barinas, Roblecito and

Anaco in my’58 Ford Station Wagon, crossing the El

Áquila páramo. Along the way we came across a

similar ’58 Ford Por Puesto with a punctured tire

and a flat spare. I lent the driver my spare and

together we went to the next village where he got

his tires fixed and I my spare back. It was a

natural thing to do in the Andes, but I doubt that I

would have stopped for this reason anywhere further

east.

We also picked up a group of red-cheeked school kids

in their ponchos and alpargatas (Woven sandals with

soles made of worn out tires) who were on their way

to school. I am sure they arrived at least an hour

early that morning!

On the highest point of the voyage, at the Pico

Áquila, I got out of the car and took a picture of

my wife with the snow covered peaks in the

background. I will never forget how I had to huff

and puff to walk back to the car at that altitude!

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Venezuela

by Air

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

When

I arrived in Venezuela, three airlines served

the interior routes of the country:

|

• Línea

Aeropostal

Venezolana (LAV),

the

government

owned

airline. It

started

business in

the late

thirties

using new

twin engined

Lockheed

Electras,

the kind of

plane used

by Amelia

Earhart.

Later they

converted to

DC-3s,

Martin 202s

and Vickers

Viscount

turboprops.

They had two

model 049

Lockheed

Constellations,

the “Simón

Bolivar” and

the

“Francisco

de Miranda”

flying

between New

York and

Maiquetía,

later

replaced by

two Super

Constellations,

one of which

crashed

after taking

off from New

York.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lockheed Electra

|

DC-3

|

Martin 202

|

Vickers Viscount

|

Constellation

|

|

Eventually LAV joined

with KLM in

a joint venture called VIASA serving

international routes.

Some of their jets were

painted with KLM livery

on one side and VIASA livery

on the other.

LAV eventually

went out of business,

but I believe it has

been resuscitated as a

domestic carrier.

There seemed to have

been a great deal of

official corruption

involved, especially

during the Pérez Jimenez

years.

On one flight between

Caracas and Barinas,

the LAV DC-3

that I was on having

started the leg to

Barquisimeto returned to

Puerto Cabello being low

on fuel. The pilot asked

the passengers for money

to fill up the tanks as

the local fuel supplier

would not give LAV credit,

but found no takers. We

then returned to

Maiquetía, filled up and

started all over again

making it safely to

Barinas, late, but

there, as the comedian

Shelley Berman used to

say!

|

|

|

• Aerovias

Venezolanas S.A. (AVENSA),

originally a subsidiary of Pan

American World Airways.

Service started with DC-3s, then

a few DC-4s joined the fleet

flying between Maracaibo and

Maiquetía, succeeded by Convair

440s and Fokker F-27s. At some

point Avensa became

independent of PanAm and

used DC-6s and then DC-9s to

serve some national and

international routes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DC-4

|

Convair 440

|

Fokker F-27

|

DC-6

|

DC-9

|

| |

|

It was

probably the preferred airline

to use due to its connection

with PanAm.

|

|

|

• Transportes

Aéreas Centroamericanos C.A. (TACA)/TACA

de Venezuela. This

airline and its DC-3s were

fairly popular, but I believe TACA

de Venezuela was

bought out by LAV in

1958.

|

|

|

• Rutas

Aéreas Nacionales S.A. (RANSA)

was a cargo airline that flew

C-46s between Miami and

Venezuela.

|

|

|

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

Photos From

Later Years

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

|

|

|

These

two ladies are my wife Judy and oldest

daughter Lynn - 1960.

|

|

|

|

USSI Ltd./Oilwell Office -

Anaco. Our two Venezuelan employees in 1960.

The camp was on the Carretera Negra next to

our competitor - National Supply.

Both camps still exist, but Oilwell and National of

course have merged and they use what was

the National facility now.

|

|

|

|