|

| |

Home

Ondas del Lago

Ondas del Lago

Contributed Content

Contributed Content

Bernie Hegglund Bernie Hegglund

This interesting Tulsa newspaper article, which is now over 50

years old, describes a flight over Motilone country on a CREOLE DC-3. It was

generously contributed by Bernard “Bernie” Hegglund.

Bernie's father, Herbert B. “Shorty“ Hegglund, first arrived in Venezuela in the

1930's where he was employed by the CREOLE PETROLEUM CORPORATION. He stayed with

the company for 31 years, during which time the Hegglunds lived all over

Venezuela - with the exception of Amuay and La Salina - including Coro, Cumarebo,

the oil camps of eastern Venezuela, Lagunillas, Tia Juana, Maracaibo, and

Caracas. “Shorty” Hegglund was the Western Division Manager for CREOLE in

Maracaibo for many years in the 1950's and '60's, and Bernie spent many of his

teenage years there. Later, “Shorty” served on the CREOLE Board of Directors

before he retired around 1967.

As the Tulsa Tribune newspaper has long since disappeared (having shut down in

the early 1990's), this fascinating article, written long before today's

attitudes of cultural and environmental preservation, could easily have been

lost forever. I'm extremely grateful to Bernie not only for having preserved it,

but for allowing me to share it here, along with a personal photograph, for all

of us to enjoy.

Plane Takes Tribune Editor Over Primitive Area of the Motilone

Indians

Deep in the Jungle, He Sees Haunts of Truly Wild Men

The Tulsa Tribune, July 21, 1952

Original article written by Jenkin Lloyd Jones

“MARACAIBO, Venezuela - I have had a rare and exciting privilege.

“I have looked down upon the settlements of wild men.

“True wild men - savages who are neither in contact with or influenced by what

we laughingly call 'civilization' - are almost extinct. Nearly everywhere the

white man's gun has overwhelmed them. The white man's greed for trade has sought

them out in their wilderness and dragged them to the market place.

“The white man's zeal for reform, for proselyting his faith, for forcing the

world to conform to his concepts of decency and conduct has dug the wild man out

of the jungle, the desert and the tundra, put him in pants and his women in

Mother Hubbards, and hailed him into Sunday school.

“Only in a few spots on earth has the wild man maintained himself. Mostly he has

done so by the remoteness of his home. The dense jungles on the upper Congo hide

pygmy tribes that explorers have never found. In the steaming Amazon empire

thousands of Indians along the sluggish and unimportant tributaries have never

been sought out by trader, scientist or clergyman. The inaccessible swamps

guarding the Darien country of south Panama have kept a segment of the San Blas

tribe proudly isolated.

“But the most remarkable wild men on earth today are probably the Motilone

Indians of western Venezuela and eastern Colombia. For here are Indians who are

neither neglected nor remote. Some of their settlements lie within 125 miles of

Maracaibo's quarter of a million people. Many attempts have been made to trade

with them and to missionize them. All overtures have been rebuffed, often

bloodily.

“The Motilone has no firearms, but he is an expert bow-man. His six-foot arrows,

often many-pronged, are designed to break in the wound and leave the barbs to

fester.

“A few years ago a Capuchin priest established a mission on the headwaters of

the Tucuco river west of Lake Maracaibo. He was determined to make friends with

the Motilones. As a result of his persuasion, planes belonging both to the

Venezuelan government and the Creole Petroleum Corp, flew him low over the

jungle huts of the tribe. He dropped fishhooks, bolts of cloth, needles-useful

things - and with them he dropped his own picture in the belief that when he

would visit them they would recognize him as a benefactor.

“Bravely, he tried to persuade the fliers to drop him by parachute into a

Motilone clearing. They refused to be a party to his death. At last one of his

assistants, attempting to penetrate A jungle trall, was ambushed and killed. The

airlift brought no evidence that the Motilones appreciated or even understood

the gesture. Today the missionary is gone and the little mission on the edge of

the great green jungle stands empty.

“TIME MAGAZINE LAST MONTH

described how two Motilone youths had recently been captured over on the

Colombian side of the boundary mountains. They snarl and spit at their captors,

although they are treated with kindness. Language experts, eavesdropping on

their whispered conversations, are trying to piece together some idea of the

language.

“It was at the suggestion of the dynamic Dr. Guillermo Zuloaga, director of

Creole, that we went calling on the Motilones. The Creole DC-3 was baking on the

kilometer-long airstrip at Lagunillas in the oilfields on the east shore of Lake

Maracaibo. It seemed like a fine afternoon for a joyride, for we had an ace

flight crew and the Creole executives - light-hearted guys like Ev Bauman, Zeb

Mayhew, Shorty Hegglund and Herb Pinilla - were eager for the adventure.

“We headed out over the lake, across 65 miles of water. At last, against a

backdrop of tall afternoon thunderheads, the shore moved toward us with green

plains and grazing cattle behind it. Slowly the settlements thinned out and

disappeared.

“A green mat of jungle flowed under us - flat jungle without hills or breaks.

Above the carpet of vine-choked trees, tall coconut palms and an occasional

stately ceiba tree appeared. Here and there a milk chocolate stream or river

twisted across the featureless land.

“At length a narrow dirt road cut down through the wilderness from the northwest

and suddenly below us was a large clearing and an oil derrick.

“'We built that road and that's our wildcat',” Dr. Zuloaga told us. 'It wasn't a

successful well, but it showed promise. This was the first well on the

Venezuelan side of the mountains that was built in what had always been regarded

as Motilone territory.'”

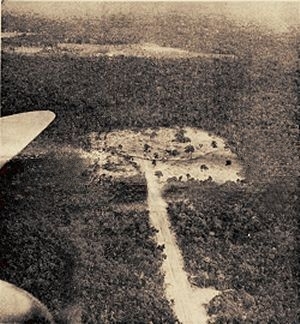

“The trail continued south and we followed it a few miles to a clearing, equally

large.

“'There's where we spudded in our second wildcat this week,' the doctor said.

'We've got that clearing as wide in radius as the average bowshot and the night

engineer is protected by screening. There's been no trouble yet, but we're leary

of the night of the new moon. If the Motilones attack it will be then when the

light is dimmest.'”

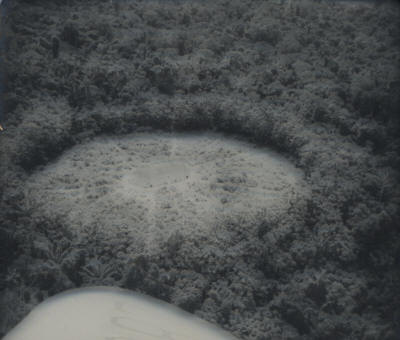

“Three minutes flying time south of the second well we picked up the first

Motilone hut. It was a giant bamboo structure about 100 feet long and 40 feet

high set in a clearing from which eight paths radiated like spokes of a wheel

into the jungle.

|

|

“OUT OF BOWSHOT - This clearing around this Creole Petroleum

Corp. wildcat well on the outer edge of the Motilone country has a

slightly greater radius than an Indian bowshot. Drillers fear the night

of the new moon when Indians like to strike. The night engineer is

protected by steel gratings.” |

“A mile away was another clearing - apparently a communal farm. We could see

corn, bananas and platina plants growing. A species of yucca was being

cultivated. The great house in the first clearing seemed to accommodate a whole

village. Why the field was cleared so far away we could no understand. No one

could guess where the geometrical paths led after the jungle gulped them.

“We rose in the air like a hungry buzzard seeking new quarry. Twenty miles away

we spotted another clearing. The great house in the center was a duplicate of

the first.

“The big plane shook the bamboo rafters as it roared 150 feet above the ridge

pole. We banked sharply, crowding the windows with our cameras, and dragged the

hut again. Not a single Motilone appeared.

|

|

“NO WELCOME MAT- Our DC-3 drags a bamboo communal house of

Venezuela's wild Motilone Indians at near tree-top level. The Indians

remain hidden inside. Paths radiate like wheel spokes through the

clearing and into the thick jungle. Puzzle: Why are the round cleared

fields of these mysterious people always from one to three miles from

their houses?” |

“It was the same for the next hour. We sought out and buzzed five of the

great communal houses at heart-stopping altitudes. We dragged the field

clearings. We carefully examined the rivers hoping for the sight of a fisherman

or a dugout canoe.

“There was no doubt that the houses were inhabited. The fields were planted, the

paths well-trodden. Were the strange inhabitants cowering in their great dark

pavilions, or were they cursing? Did they think the plane was a visitation from

an angry god, or did they know it contained men - hateful, busybody white men,

too curious to leave them alone and too cowardly to face their arrows?

“As the sun dipped low Into the mountains that mark the boundary of Colombia we

picked up the turbid Rio Tocuco and followed it northwest until the jungle began

to break against the foothills. We passed over the ill-fated mission and into

the lush and open cattle country beyond. This cattle country has great promise

for Venezuela, for there are hundreds of thousands of acres of high rich

grassland to be had almost for the asking.

“We thought of this potential Hereford Heaven and of the oil wildcats crowding

hard upon the stronghold of the resentful Motilones.

“When will the cattlemen to the northwest and the hardy wildcatters to the

northeast cut through the jealous isolation of these authentic wildmen? It

probably won't be long.

“A month ago in Louisiana some oil man gave the restless Dr. Zuloaga a ride in a

helicopter. The doctor's enthusiasm for helicopters now knows no bounds and he

is laying siege to the Creole board to purchase a couple. How convenient they

would be to carry men back and forth between Maracaibo and the big camps, or to

whisk geologists and engineers to the remote discovery wells!

“If the doctor ever gets his helicopters we'll bet our bottom Bolivar that

hardly a month will pass before he organizes an expedition to the Motilones.

Until now there has been no way to reach these clearings without a suicidal trek

along the jungle paths or a one-way drop by parachute.

“But the helicopter will change all this. Take a couple of flying bananas (a

type of helicopter). One could plunk down at the front door of a Motilone

mansion, disgorge an anthropologist, a language expert, two bales of glass

beads, and half a dozen Tommy gun wielding Venezuelan soldiers as moral support.

The second helicopter could hover over the whole scene to scare off any possible

counter attack from the surrounding jungle.

“What an adventure! What a story! When the great helicopter expedition

against the Motilones comes off, I want to go along - in the one that hovers.”

Another photograph of a Motilone bamboo communal hut being

over flown taken during the same flight that was not published with the article.

|